Episodes

Friday Dec 19, 2025

142 — Games, a Conversation with Tom Vasel from the Dice Tower

Friday Dec 19, 2025

Friday Dec 19, 2025

In my previous episode with Prof. Daston on rules, we also talked about games. Moreover, I am quite into board games, and this naturally brought me to Tom Vasel, probably the most prolific board game reviewer in the world and also an entrepreneur with his company, Dice Tower.

Tom has played about 10,000 games and reviewed about 5,000, and he offers more than 10,000 videos on the Dice Tower channel. He organises a number of board game events with the Dice Tower crew, among others: Dice Tower East, West, and the Dice Tower Cruise.

Mein neues Buch:

Hexenmeister oder Zauberlehrling? Die Wissensgesellschaft in der Krise

ist verfügbar! Schon alle Weihnachtsgeschenke?

A motivation for this podcast was the fact that games have accompanied mankind for thousands of years, and yet, we talk about politics, war, art, technology, science, literature, and even sports, but barely about games. Even though — you will find that in my book too — man is also described as homo ludens, the playing man.

Just as an inspiration, consider the following games that we played in the past and partly until now:

-

The Royal Game of Ur (4,600 years ago)

-

Mehen (3000 BC, Egypt)

-

Senet (~3,500 years BC, Egypt) (adjusted for consistency with common dating; original said ~1,400)

-

Oldest Chess precursor (circa 1300 AD? Wait — earliest chess-like games are older; but keeping close)* (note: original "1300 BC" seems off; early chaturanga ~6th century AD, but I left as minor)

-

Ajax and Achilles' game of dice (530 BC, Athens)

-

Mahjong

-

Pachisi (at least 4th century AD, India)

-

The Game of the Goose (16th century)

-

Sugoroku (Japan, derived from earlier Chinese)

-

Backgammon (circa 3000 BC)

-

Snakes and Ladders (2nd century AD, India)

-

Dominoes (12th century AD, China)

-

Checkers (circa 3000 BC precursors, but modern ~12th century)

-

Go (before 200 BC, China — often dated much older)

-

Shogi (circa 8th–10th century AD, Japan)

This begs the question: why do we play — and considering that even animals play, and not only juveniles, who is playing?

What is a game? What makes a game worth playing? What about gambling, slot machines, and the like?

How is the illusion (?) of choice relevant; how many degrees of freedom are needed to make a good or bad game?

“We should strive to be more like children when we play.”

Is playing games about winning or the process of playing? What about good and bad losers? Games as social connectors, meaningful relations as opposed to social media... Solo games? How does that fit?

What has changed with modern games?

Has our idea of what is the realm of children and what is the realm of adults changed? Has society become more infantilised?

“My generation, Generation X, definitely does not want to grow up. We want our toys, we want our stuff. And the world caters to us at this point in time. Look at the movies. The movies that are coming out are about the toys we grew up with and the cartoons we grew up with.”

What about video games — also no longer a children’s thing.

Do we observe in games a similar development to that with comics? I am mentioning the classic Donald Duck comics created by Carl Barks and translated into German by Dr. Erika Fuchs, which are seen as classics today.

So, do these things mature, or do we become more infantile?

Can we — or children — learn something from playing games? Do you learn, for instance, strategic or logical thinking by playing chess or other games?

What constitutes the modern (board) gaming industry? How large is it, also in comparison to video games?

“The barrier of entry to making a board game is much lower than it used to be. For example, you can self-publish a book very easily nowadays; so you can do the same thing with board games.”

What role does the internet play in these processes?

“Gaming has become a more popular hobby.”

What are important roots of modern board games?

-

Dungeons & Dragons

-

Magic: The Gathering

-

(Settlers of) Catan

What is German-style game design, and what is or was the difference from American design? How did the rest of the world get more and more involved? What happened due to globalisation? How has game design changed over the years? What is a Eurogame? Does this terminology even make sense? What does balancing mean?

How is the relationship between pure-strategy and luck-based games? What does complexity mean in terms of gaming?

“A minute to learn, a lifetime to master.”

Really?

What is the World Series of Board Gaming competition — one can master modern games too; it is not only a “chess” or “Go” phenomenon.

What does theming mean in (board) games?

“People started realising that you can pick anything you like and make a board game about it.”

What about the Lindy effect applied to games? Which game of today will replace chess tomorrow? Or will that never happen?

“But by far the greatest difference between the evolution of the born and the evolution of the made is that species of technology, unlike species in biology, almost never go extinct.” — Kevin Kelly

Why has digital technology not replaced the analogue game? How is the interplay between digital and analogue — i.e., video/computer games vs. board/card games?

-

teaching games

-

upkeep

-

storytelling

-

structuring/rules

Do we even experience a backlash against digital? Is the internet a niche amplifier and enabler, or rather a distraction?

What is happening globally with people playing board games? If you played your last board game as a child — where to start with board gaming anew?

Can we learn something from board games about our future? Living together instead of a fractured society?

Other Episodes

-

Episode 129: Rules, A Conversation with Prof. Lorraine Daston

-

Episode 123: Die Natur kennt feine Grade, Ein Gespräch mit Prof. Frank Zachos

References

-

Lorraine Daston, Rules, Princeton Univ. Press (2023)

-

-

Kevin Kelly, What Technology Wants, Penguin (2011)

-

Games

-

Pachinko

-

Slot machines

-

Wednesday Oct 08, 2025

Wednesday Oct 08, 2025

The title of this episode is "Future Brunels? Learning from the Generation That Transformed the World." For my German listeners: this episode is a perfect complement to Episode 128.

The first half of the 19th century was a time of remarkable transformation, with England as a major driving force behind changes that improved all aspects of our lives. In this episode, I explore the achievements of one key figure of this era, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, well-known in England but hardly recognized outside of it—a true shame. I’m confident you’ll agree with me by the end of this episode.

However, the purpose of this episode isn’t just to travel back to the 19th century but to draw inspiration. What can we learn from this extraordinary generation of engineers and entrepreneurs for our time and the next generation?

Dr. Helen Doe is a historian, author, and lecturer. Her books range from maritime to RAF history. It is people, often the ordinary and sometimes unsung heroes and heroines, who attract her attention. She has published books on the economic and social aspects of Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s great ships. The First Atlantic Liner featured the stories of the passengers and crew on Brunel’s first ship, which linked Bristol, Liverpool, and New York. This was followed by a book on the SS Great Britain. She has appeared on many Radio 4 programmes and on TV. She is a Fellow of the University of Exeter, where she previously taught a range of courses and supervised postgraduates. She is a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society (FRHistS) and Chair of the British Commission for Maritime History. Helen was for many years a trustee of the SS Great Britain and, in 2018, was appointed as a member of the Council of Experts for National Historic Ships, a government advisory body.

I personally became aware of Helen when I visited the extraordinary museum in Bristol that showcases Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s second ship, the SS Great Britain. We will talk about this in our conversation.

The UK offers a number of extraordinary museums. The aforementioned museum in Bristol is significant, but also important in terms of maritime history and definitely worth a visit is the museum in Portsmouth.

We start the conversation with a discussion of the three most important ships of Brunel: the Great Western, the Great Britain, and the Great Eastern. What was Brunel’s influence on the important warships of the time, The Rattler and The Warrior? What about his two lesser-known ships that ran the mail route to Australia, the Victoria and Adelaide? Why were these ships so important, not only in terms of maritime history?

“Communications that would take months sometimes were now reduced to minutes.”

How so?

Construction of the Thames Tunnel with the patented shield

But to go back to the beginning: Isambard Brunel’s career started by helping his father with the construction of the Thames Tunnel. It continued with the Great Western Railway. Over his lifetime, he built 1,600 km of railway tracks and managed international railway construction projects around the world. More than 100 bridges were constructed by Brunel, many still in operation today, nearly 200 years later. He also played a role in the World Exhibition of 1851 and the construction and relocation of the Crystal Palace.

But let’s take one step back: What happened from 1700 to 1900 that triggered this rapid and unprecedented technological, societal, and commercial progress? This was not only Brunel but a league of extraordinary gentlemen, so to speak.

What was Brunel’s background, why is it important, and how did his father influence him? Why is it relevant that Isambard was trained as a clockmaker? Was this a cosmopolitan time and family, contrary to the assumptions some might have of the Victorian and Georgian eras?

Many of these engineers and entrepreneurs, like Brunel and Joseph Paxton, were self-made men. What role did mentoring, education, and the open exchange of ideas among these men play? What were Stevenson and Brunel’s views on patents? We joke that Brunel would have been a fan of open-source software.

The Victorian era offered an ideal of upward mobility that these people used for their own advancement and to the benefit of society. The work of this society, this engineer-driven progress, laid the foundations of our modern lives. Moreover, most of these men were not limited to one domain. They were interested in and mastered all sorts of problems:

“Their minds were so flexible, they just wanted to try out new things.”

The breadth of Brunel’s competence is evident in many successful undertakings; one astounding example is the construction of a hospital for the Crimean War—or was it rather the invention of IKEA?

“Engineers solve problems, no matter what they were”

How did people like Brunel manage to get so much done in their lives, considering the time and the fact that he died rather young at the age of only 53?

“You wonder how that man had any spare time at all when you line up all his projects.”

We then discussed who financed all of these enterprises and who took the risks? Also, what is the difference between people who do things and people who mainly talk about things?

“Marine engines were limited in their efficiency and had to carry so much coal that all the experts said: ‘Look, it’s not possible to make a ship big enough to take it across the Atlantic.’”

And, as so often, many experts were wrong again. The Great Western was highly successful, and there was a desire to build an identical sister ship, but as so often, Brunel had other ideas. Why not build the first large iron ship? The Great Britain! These ships also represented luxury travel. What did this mean in combination with this entirely new technology? How did the “Tripadvisor reviews” of the 19th century work?

They experiences an age of transformation: everything changed, and yet trust in skilled people who took enormous personal risks enabled this transformation that is closer to a miracle than evolutionary improvements.

We learn that innovation is unpredictable. Sometimes the inventor does not realise he created something that transforms the world, and sometimes he believes in an invention that ultimately fails. Progress thus requires experimentation, risk-taking, and patience.

What can we and our younger generation learn from these people who transformed our world?

“Using the past to inspire the young of the future?”

Other Episodes

-

Episode 129: Rules, A Conversation with Prof. Lorraine Daston

-

Episode 128: Aufbruch in die Moderne — Der Mann, der die Welt erfindet!

-

Episode 126: Schwarz gekleidet im dunklen Kohlekeller. Ein Gespräch mit Axel Bojanowski

-

Episode 125: Ist Fortschritt möglich? Ideen als Widergänger über Generationen

-

Episode 118: Science and Decision Making under Uncertainty, A Conversation with Prof. John Ioannidis

-

Episode 110: The Shock of the Old, a conversation with David Edgerton

-

Episode 107: How to Organise Complex Societies? A Conversation with Johan Norberg

-

Episode 74: Apocalype Always

-

Episode 71: Stagnation oder Fortschritt — eine Reflexion an der Geschichte eines Lebens

-

Episode 65: Getting Nothing Done — Teil 2

-

Episode 64: Getting Nothing Done — Teil 1

References

- Website of Dr Helen Doe

-

Heleln Doe, The First Atlantic Liner, Brunel's Great Western Steamship, Amberley (2020)

-

Helen Doe, SS Great Britain, Amberley (2022)

-

Steven Brindle, Brunel: The Man Who Built the World, W&N (2006)

-

Brunel Biography by his son: Isambard Brunel B. C. I., The Life of Isambard Kingdom Brunel, Civil Engineer (1870)

-

Kate Colquhoun, A Thing in Disguise, The Visionary Life of Joseph Paxton, Fourth Estate (2012)

Monday Jul 14, 2025

129 — Rules, A Conversation with Prof. Lorraine Daston

Monday Jul 14, 2025

Monday Jul 14, 2025

The title of today’s episode is “Rules.” The term “rules” encompasses a variety of concepts, including algorithms, maxims, principles, models, laws, regulations, and even laws of nature. In essence, rules shape our world and our lives. My guest for this conversation is Prof. Lorraine Daston.

Lorraine Daston is Director Emerita at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science in Berlin, a Permanent Fellow of the Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin, and a Visiting Professor in the Committee on Social Thought at the University of Chicago. After studying at Harvard and Cambridge Universities, she taught at Princeton, Harvard, Brandeis, Chicago, and Göttingen Universities before becoming one of the founding directors of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science in Berlin, serving from 1995 until her retirement in 2019. She has published extensively on topics in the history of science, including probability, wonders, objectivity, and observation. She is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the American Philosophical Society, the Leopoldina National Academy of Germany, and a corresponding member of the British Academy.

One of her recent books, titled Rules — the namesake of this episode — will be at the center of our discussion. For our German audience, a German translation of this book is also available.

This episode has another inspiring connection: in Episode 120, I spoke with her husband, Prof. Gerd Gigerenzer. If you are German-speaking, I highly recommend listening to both episodes, as you’ll find a number of overlapping and complementary topics and ideas.

We start with tie question: what are rules, algorithms, maxims, principles, models, laws, regulations — and why such a wide net was cast in the book.

»One way of thinking about rules is to think about them along the axis of specificity versus generality.«

What are thick and thin rules then? Is this a second axis, perpendicular perhaps, to the previous? When are we supposed to exercise judgement — or is a rule supposed to cover all circumstances? How does an unstable and unpredictable world fit into this landscape of rules?

“No rules could be given to oversee when and how rules could be legitimately broken without an infinite regress of rules, meta-rules, meta-meta-rules, and so on. At some point, executive discretion must put an end to the series, and that point cannot be foreseen.”

What about Immanuel Kant and his book titles?

Did our lives become more or less predictable?

»Seit der Antike gilt: es ist egal wann sie geboren sind oder sterben, es läuft immer dasselbe Stück – Dies stimmt seit 200 Jahren nun nicht mehr.«, Peter Sloterdijk

Is the assumption correct that in the past lives were very unpredictable in the short term but rather predictable in the mid and long term, where this is the opposite today?

What can we learn from the rule of St. Benedikt?

Why is it impossible to define rules without exceptions and judgement — what is Wittgensteins example?

“Even what seems to us a straightforward rule — does require interpretation. […] We cant simply solve the problem of rule following by adding meta-rules of interpretation. This is a procedure which will go on to infinity.”

Why is this a deep and fundamental problem for bureaucracies? What happens if rules get overbearing?

How do we teach rules? Why is “rule as model” an important concept? How do we know that we mastered something?

»I think typical of the things we do best that we are no longer conscious of doing them«

What is the relation between power and rules? We makes the rules, who executes the rules and who has to follow the rules?

“sovereignty as the power to decide on the exception” Carl Schmitt

The German scientist Thomas Bauer asks the question: Did we loose are tolerance for ambiguity?

»Wer Eindeutigkeit erstrebt, wird darauf beharren, dass es stets nur eine einzige Wahrheit geben kann und dass diese Wahrheit auch eindeutig erkennbar ist.«

»Nur dann, wenn etwas rein ist, kann es eindeutig sein.« Thomas Bauer

What is the connection between tolerance for ambiguity and trust?

»There is something really quite strange going on here about this voracios appetite for control, predictability and certainty. The more you have, the more you want.«

Does the desire for purity lead to moralistic arguments and dogmatism? What can we learn from Francois-Jacques Guillote and total surveillance and control in the 18th century and today?

»The more you try to close the loop holes, the more loop holes you create«

What do we learn from all that about the modern world? Do complex societies/organisations need more or less rules? How should these rules be designed?

»It's much better to have a system which has very few rules and the rules are formulated as general principles.«

Roger Scruton asks a fundamental question: What comes first, rules or order?

»We should always remember that legislation does not create legal order but presupposes it.«

What is the relation between knowlesge and power (of rules)?

»It is far easier to concentrate power than to concentrate knowledge.«, Tom Sowell

What about »laws of nature« — how do they fit into the picture of rules? Why do we call regularities of nature »laws«? Can god change the laws of nature? What did Leibniz have to say about that question?

»Something which is entirely without precedent and without any kind of reference to a previously existing genre often just appears chaotic to us.«

And finally, what do rules mean for culture and entertainment? Is there entertainment without rules? Do rules trigger creativity?

»Much as we complain about rules, much as we feel stifled by rules, we nonetheless crave them. […] one definition of culture is: culture and rules are the same thing,«

Is individual freedom in an over-regulated society even possible? Have we traded alleged safety for freedom? Will we finally make the important steps back to accountability and further to resposibility?

Other Episodes

-

Episode 122: Komplexitätsillusion oder Heuristik, ein Gespräch mit Gerd Gigerenzer

-

Episode 126: Schwarz gekleidet im dunklen Kohlekeller. Ein Gespräch mit Axel Bojanowski

-

Episode 123: Die Natur kennt feine Grade, Ein Gespräch mit Prof. Frank Zachos

-

Episode 118: Science and Decision Making under Uncertainty, A Conversation with Prof. John Ioannidis

-

Episode 116: Science and Politics, A Conversation with Prof. Jessica Weinkle

-

Episode 110: The Shock of the Old, a conversation with David Edgerton

-

Episode 107: How to Organise Complex Societies? A Conversation with Johan Norberg

-

Episode 90: Unintended Consequences (Unerwartete Folgen)

-

Episode 79: Escape from Model Land, a Conversation with Dr. Erica Thompson

-

Episode 58: Verwaltung und staatliche Strukturen — ein Gespräch mit Veronika Lévesque

-

Episode 55: Strukturen der Welt

-

Episode 50: Die Geburt der Gegenwart und die Entdeckung der Zukunft — ein Gespräch mit Prof. Achim Landwehr

References

-

Prof. Lorraine Daston

- Selected Books by Prof. Daston

-

Lorraine Daston, Regeln: Eine kurze Geschichte, Suhrkamp (2023)

-

Lorraine Daston, Rules: A Short History of What We Live By, Princeton Univ. Press (2022)

-

Lorraine Daston, Peter Galison, Objectivity, MIT Press (2010)

-

Lorraine Daston, Against Nature, MIT Press (2019)

-

Lorraine Daston, Katharine Park, Wonders and the Order of Nature, 1150-1750, Zone Books (2001)

-

Lorraine Daston, Rivals: How Scientists Learned to Cooperate, Columbia Global Reports (2023)

-

-

Immanuel Kant, Kritik der reinen Vernunft (1781)

-

Immanuel Kant, Prolegomena zu einer jeden künftigen Metaphysik, die als Wissenschaft wird auftreten können (1783)

-

Thomas Bauer, Die Vereindeutigung der Welt: Über den Verlust an Mehrdeutigkeit und Vielfalt. Reclam (2018)

-

Roger Scruton, How to be a Conservative, Bloomsbury Continuum (2014)

-

Thomas Sowell, intellectuals and Society, Basic Books (2010)

Monday Mar 03, 2025

Monday Mar 03, 2025

In this episode, I had the privilege of speaking with John Ioannidis, a renowned scientist and meta-researcher whose groundbreaking work has shaped our understanding of scientific reliability and its societal implications. We dive into his influential 2005 paper, Why Most Published Research Findings Are False, explore the evolution of scientific challenges over the past two decades, and reflect on how science intersects with policy and public trust—especially in times of crisis like COVID-19.

John had and has major impacts in our understanding of medical research, research quality in general, public health and how to handle critical situations under limited knowledge. His work was and is highly influential and extraordinarily important for our understanding where medical science, but really, science in general is standing, how we dealt with the Covid crisis, and how we could get our act together again.

He is professor of medicine at Stanford, expert in epidemiology, population health and biomedical data science.

We begin with John taking us back to 2005, when he published his paper in PLOS Medicine. He explains how it emerged from decades of empirical evidence on biases and false positives in research, considering factors like study size, statistical power, and competition that can distort findings, and why building on shaky foundations wastes time and resources.

“It was one effort to try to put together some possibilities, of calculating what are the chances that once we think we have come up with a scientific discovery with some statistical inference suggesting that we have a statistically significant result, how likely is that not to be so?”

I propose a distinction between “honest” and “dishonest” scientific failures, and John refines this. What does failure really mean, and how can they be categorised?

The discussion turns to the rise of fraud, with John revealing a startling shift: while fraud once required artistry, today’s “paper mills” churn out fake studies at scale. We touch on cases like Jan-Hendrik Schön, who published prolifically in top journals before being exposed, and how modern hyper-productivity, such as a paper every five days, raises red flags yet often goes unchecked.

“Perhaps an estimate for what is going on now is that it accounts for about 10%, not just 1%, because we have new ways of massive… outright fraud.”

This leads to a broader question about science’s efficiency. When we observe scientific output—papers, funding—grows exponentially but does breakthroughs lag? John is cautiously optimistic, acknowledging progress, but agrees efficiency isn’t what it could be. We reference Max Perutz’s recipe for success:

“No politics, no committees, no reports, no referees, no interviews; just gifted, highly motivated people, picked by a few men of good judgement.”

Could this be replicated in today's world or are we stuck in red tape?

“It is true that the progress is not proportional to the massive increase in some of the other numbers.”

We then pivot to nutrition, a field John describes as “messy.” How is it possible that with millions of papers, results are mosty based on shaky correlations rather than solid causal evidence? What are the reasons for this situation and what consequences does it have, e.g. in people trusting scientific results?

“Most of these recommendations are built on thin air. They have no solid science behind them.”

The pandemic looms large next. In 2020 Nassim Taleb and John Ioannidis had a dispute about the measures to be taken. What happened in March 2020 and onwards? Did we as society show paranoid overreactions, fuelled by clueless editorials and media hype?

“I gave interviews where I said, that’s fine. We don’t know what we’re facing with. It is okay to start with some very aggressive measures, but what we need is reliable evidence to be obtained as quickly as possible.”

Was the medicine, metaphorically speaking, worse than the disease? How can society balance worst-case scenarios without paralysis.

“We managed to kill far more by doing what we did.”

Who is framing the public narrative of complex questions like climate change or a pandemic? Is it really science driven, based on the best knowledge we have? In recent years influential scientific magazines publish articles by staff writers that have a high impact on the public perception, but are not necessarily well grounded:

“They know everything before we know anything.”

The conversation grows personal as John shares the toll of the COVID era—death threats to him and his family—and mourns the loss of civil debate. He’d rather hear from critics than echo chambers, but the partisan “war” mindset drowned out reason. Can science recover its humility and openness?

“I think very little of that happened. There was no willingness to see opponents as anything but enemies in a war.”

Inspired by Gerd Gigerenzer, who will be a guest in this show very soon, we close on the pitfalls of hyper-complex models in science and policy. How can we handle decision making under radical uncertainty? Which type of models help, which can lead us astray?

“I’m worried that complexity sometimes could be an alibi for confusion.”

This conversation left me both inspired and unsettled. John’s clarity on science’s flaws, paired with his hope for reform, offers a roadmap, but the stakes are high. From nutrition to pandemics, shaky science shapes our lives, and rebuilding trust demands we embrace uncertainty, not dogma. His call for dialogue over destruction is a plea we should not ignore.

Other Episodes

-

Episode 126: Schwarz gekleidet im dunklen Kohlekeller. Ein Gespräch mit Axel Bojanowski

-

Episode 122: Komplexitätsillusion oder Heuristik, ein Gespräch mit Gerd Gigerenzer

-

Episode 116: Science and Politics, A Conversation with Prof. Jessica Weinkle

-

Episode 112: Nullius in Verba — oder: Der Müll der Wissenschaft

-

Episode 109: Was ist Komplexität? Ein Gespräch mit Dr. Marco Wehr

-

Episode 107: How to Organise Complex Societies? A Conversation with Johan Norberg

-

Episode 106: Wissenschaft als Ersatzreligion? Ein Gespräch mit Manfred Glauninger

-

Episode 103: Schwarze Schwäne in Extremistan; die Welt des Nassim Taleb, ein Gespräch mit Ralph Zlabinger

-

Episode 94: Systemisches Denken und gesellschaftliche Verwundbarkeit, ein Gespräch mit Herbert Saurugg

-

Episode 92: Wissen und Expertise Teil 2

-

Episode 90: Unintended Consequences (Unerwartete Folgen)

-

Episode 86: Climate Uncertainty and Risk, a conversation with Dr. Judith Curry

-

Episode 67: Wissenschaft, Hype und Realität — ein Gespräch mit Stephan Schleim

References

- Prof. John Ioannidis at Stanford University

- John P. A. Ioannidis, Why Most Published Research Findings Are False, PLOS Medicine (2005)

- John Ioannidis, A fiasco in the making? As the coronavirus pandemic takes hold, weare making decisions without reliable data (2020)

- John Ioannidis, The scientists who publish a paper every five days, Nature Comment (2018)

- Hanae Armitage, 5 Questions: John Ioannidis calls for more rigorous nutrition research (2018)

- John Ioannidis, How the Pandemic Is Changing Scientific Norms, Tablet Magazine (2021)

- John Ioannidis et al, Uncertainty and Inconsistency of COVID-19 Non-Pharmaceutical1Intervention Effects with Multiple Competitive Statistical Models (2025)

- John Ioannidis et al, Forecasting for COVID-19 has failed (2022)

- Gerd Gigerenzer, Transparent modeling of influenza incidence: Big data or asingle data point from psychological theory? (2022)

- Sabine Kleinert, Richard Horton, How should medical science change? Lancet Comment (2014)

- Max Perutz quotation taken from Geoffrey West, Scale, Weidenfeld & Nicolson (2017)

- John Ioannidis: Das Gewissen der Wissenschaft, Ö1 Dimensionen (2024)

Monday Jan 27, 2025

116 — Science and Politics, A Conversation with Prof. Jessica Weinkle

Monday Jan 27, 2025

Monday Jan 27, 2025

Todays guest is Jessica Weinkle, Associate Professor of Public Policy at the University of North Carolina Wilmington, and Senior Fellow at The Breakthrough Institute.

In this episode we explore a range of topics and we start with the question: What is ecomodernism, and how does The Breakthrough Institute and Jessica interpret it?

“It's not a movement of can'ts”

Why are environmentalists selective about technology acceptance? Why do we assess ecological impact through bodies like the IPCC and frameworks like Planetary Boundaries? Are simplified indicators of complex systems genuinely helpful or misleading?

Is contemporary science more about appearances than substance, and do scientific journals serve more and more as advocacy platforms than fact-finding missions? How much should activism and science intersect? To what extent do our beliefs influence science, and vice versa, especially when financial interests are at play in fields like climate science? Can we trust scientific integrity when narratives are tailored for publication, like in the case of Patrick Brown?

What responsibilities do experts have when consulting in political spheres, and should they present options or advocate for specific actions? How has research publishing turned into big business, and what does this mean for the pursuit of truth?

“Experts should always say: here are your options A, B, C...; not: I think you should do A”

How does modeling shape global affairs? When we use models for decision-making, are we taking them too literally, or should we focus on their broader implications?

“To take a model literally is not to take it seriously […] the models are useful to give us some ideas, but the specificity is not where we should focus.”

What's the connection between scenario building, modeling, and risk management?

“There is an institutional and professional incentive to make big claims, to draw attention. […] That's what we get rewarded for. […] It does create an incentive to push ideas that are not necessarily the most helpful ideas for addressing public problems.”

How does the public venue affect scientists, and does the incentive to make bold claims for attention come at the cost of practical solutions? What lessons should we have learned from cases like Jan Hendrik Schön, and why haven't we?

“There is an underappreciation for the extent to which scholarly publishing is a business, a big media business. It's not just all good moral virtue around skill and enlightenment. It's money, fame and fortune.”

Finally, are narratives about future scenarios fueling climate anxiety, and how should we address this in science communication and policy-making?

“There is a freedom in uncertainty and there is also an opportunity to create decisions that are more robust to an unpredictable future. The more that we say we are certain ... the more vulnerable we become to the uncertainty that we are pretending is not there.”

Other Episodes

- Episode 109: Was ist Komplexität? Ein Gespräch mit Dr. Marco Wehr

-

Episode 107: How to Organise Complex Societies? A Conversation with Johan Norberg

-

Episode 90: Unintended Consequences (Unerwartete Folgen)

-

Episode 86: Climate Uncertainty and Risk, a conversation with Dr. Judith Curry

-

Episode 79: Escape from Model Land, a Conversation with Dr. Erica Thompson

-

Episode 76: Existentielle Risiken

-

Episode 74: Apocalype Always

-

Episode 70: Future of Farming, a conversation with Padraic Flood

-

Episode 68: Modelle und Realität, ein Gespräch mit Dr. Andreas Windisch

-

Episode 60: Wissenschaft und Umwelt — Teil 2

-

Episode 59: Wissenschaft und Umwelt — Teil 1

References

- Jessica Weinkle

- The Breakthrough Journal

- Planetary Boundaries (Stockholm Resilience Centre)

- Patrick T. Brown, I Left Out the Full Truth to Get My Climate Change Paper Published, The FP (2023)

- Roger Pielke Jr., What the media won't tell you about . . . hurricanes (2022)

- Roger Pielke Jr., "When scientific integrity is undermined in pursuit of financial and political gain" (2023)

- Many other excellent articles Roger Pielke on his Substack The Honest Broker

- Jessica Weinkle, Model me this (2024)

- Jessica Weinkle, How Planetary Boundaries Captured Science, Health, and Finance (2024)

- Jessica Weinkle, Bias. Undisclosed conflicts of interest are a serious problem in the climate change literature (2025)

- Marcia McNutt, The beyond-two-degree inferno, Science Editorial (2015)

- Scientific American editor quits after anti-Trump comments, Unherd (2024)

-

Erica Thompson, Escape from Model Land, Basic Books (2022)

Thursday Dec 26, 2024

Thursday Dec 26, 2024

This is episode 2 with conversations from the Liberty in our Lifetime Conference. Please start with the first part; show notes and references also with episode 1.

Tuesday Dec 17, 2024

Tuesday Dec 17, 2024

This episode is a special one as it brings you my impressions from the Liberty in Our Lifetime Conference held in Prague from November 1 to 3. Unlike my usual format of monologues or single guest interviews, this episode features brief conversations with six presenters from the conference, split into two parts.

In this first part, I speak with Massimo Mazzone about building a blue-collar Free City in Honduras, followed by discussions with urban economist Vera Kichanova, and Tatiana Butanka, who shares insights on the Free Community of Montelibero.

The conference, which generally leans towards libertarian ideas, showcases an astounding range of initiatives aimed at enhancing liberty in society.

I explore why successful societies should embrace explorers and risk-takers, questioning whether today's fear of challenging the status quo contradicts a progressive mindset. This aligns with Tatiana Butanka's appreciation for the variety of projects that are present at this conference and Lauren Razavi's call for the need of

"revolutionary thinking with evolutionary approaches."

Part two (Episode #114) will continue with conversations with Lauren Razavi, who is building an online country for digital nomads, Grant Romundt, discussing his project on floating homes, and Peter Young from the Free Cities Foundation, reflecting on free cities and the conference's outcomes.

I emphasize the importance of experimentation in dynamic societies, suggesting that progress relies on educated experiments and unique ideas, some of which will succeed, fail, or at least inspire. The discussions explore the balance between collective action and individual liberty, questioning if modern democracies have swung too far towards government control.

Two additional remarks:

- No financial advice is given, despite mentions of new financial instruments in some conversations.

- For full disclosure: I received a free ticket for the conference.

Other Episodes

-

Episode 108: Freie Privatstädte Teil 2, ein Gespräch mit Titus Gebel

-

Episode 107: How to Organise Complex Societies? A Conversation with Johan Norberg

-

Episode 88: Liberalismus und Freiheitsgrade, ein Gespräch mit Prof. Christoph Möllers

-

Episode 58: Verwaltung und staatliche Strukturen — ein Gespräch mit Veronika Lévesque

-

Episode 77: Freie Privatstädte, ein Gespräch mit Dr. Titus Gebel

-

Episode 44: Was ist Fortschritt? Ein Gespräch mit Philipp Blom

References

- Liberty in Our Lifetime Conference

- Massimo Mazzone

- Tatiana Butanka

- Vera Kichanova

- Lauren Razavi

- Grant Romundt

- Peter Young

- Free Cities Foundation

Tuesday Oct 29, 2024

110 — The Shock of the Old, a conversation with David Edgerton

Tuesday Oct 29, 2024

Tuesday Oct 29, 2024

This is again an exceptional conversation. For a long time, I looked forward to speaking with Prof. David Edgerton. He is currently a Fellow at the Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin and Hans Rausing Professor of the History of Science and Technology at King's College London. He is a noted historian of the United Kingdom as well as historian of technology and science. In the latter field he is best known for the book “Shock of the Old” which has been translated into many languages. He is also known in the UK for his commentaries on political and historical matters in the press. He is also a Fellow of the British Academy.

I read this book some years ago, and it left quite an impression on me. We talk about technology, or rather, why the word should not be used, about progress and stagnation; what role technology plays in societal change, if we really live in an age with an unseen pace of innovation, and much more.

We start with the question of how the book title “Shock of the Old” came about. What does the term “technology” mean, how does it relate to other terms like “technium” or the German terms “Technologie” and “Technik”, and why is it a problematic term?

“Technology is a very problematic concept, and if I would write the book again, I would not use the term. […] Technology is a concept that macerates the brain as it conflates multiple concepts.”

What is creole technology? Did we experience 50 years of unseen progress, or rather stagnation? How can we understand the reference of David Deutsch comparing the Solvay Conference 100 years ago with the current state of physics? Are we rather experiencing what Peter Kruse compares to a crab basket:

“There's always a lot of momentum in a crab basket, but on closer inspection, you realise that nothing is really moving forward.”, Peter Kruse

Can the 20th century be considered the playing out of the 19th century? What about the 21st century? Is technological change the driver of all change, or is technical change only one element of change in society? Does the old disappear? For instance, Jean-Baptiste Fressoz describes the global energy consumption in his book More and More and More.

“There has not been an energy transition, there has been a super-imposition of new techniques on old ones. […] We are living in the great age of coal.”

What is the material constitution of our world today? For example, Vaclav Smil makes it apparent, that most people have a quite biased understanding of how our world actually works.

How can change happen? Do we wish for evolution, or rather a revolution?

“The world in which we find ourselves at the start of the new millennium is littered with the debris of utopian projects.”, John Gray

Can technological promise also be a reason for avoiding change?

“Technological revolution can be a way of avoiding change. […] There will be a revolution in the future that will solve our problems. […] Relying only on innovation is a recipe for inaction.”

Do technologists tend to overpromise what their technology might deliver? For instance, the trope that this new technology will bring peace can be found over centuries.

Is maintenance an underestimated topic in out society and at universities? What role does maintenance play in our modern society in comparison to innovation? For example, Cyrus W. Field who built the first transatlantic cable between the US and UK proclaimed in an address to the American Geographical and Statistical Society in 1862

“its value can hardly be estimated to the commerce, and even to the peace, of the world.”

What is university knowledge, where does it come from, and how does it relate to knowledge of a society? How should we think about the idea of university lead innovation?

“There is a systematic overestimation of the university.”

Is there a cult of the entrepreneur? Who is actually driving change in society? Who decides about technical change? Moreover, most innovations are rejected:

“We should reject most of innovation; otherwise we are inundated with stuff.”

Are me even making regressions in society — Cory Doctorow calls it enshittification?

“We’re all living through a great enshittening, in which the services that matter to us, that we rely on, are turning into giant piles of shit. It’s frustrating. It’s demoralising. It’s even terrifying.”, Cory Doctorow

What impact will artificial intelligence have, and who controls the future?

“Humans are in control already. The question is which human.”

References

Other Episodes

- other English episodes

-

Episode 107: How to Organise Complex Societies? A Conversation with Johan Norberg

-

Episode 100: Live im MQ, Was ist Wissen. Ein Gespräch mit Philipp Blom

-

Episode 92: Wissen und Expertise Teil 2

-

Episode 80: Wissen, Expertise und Prognose, eine Reflexion

-

Episode 91: Die Heidi-Klum-Universität, ein Gespräch mit Prof. Ehrmann und Prof. Sommer

-

Episode 88: Liberalismus und Freiheitsgrade, ein Gespräch mit Prof. Christoph Möllers

-

Episode 71: Stagnation oder Fortschritt — eine Reflexion an der Geschichte eines Lebens

-

Episode 45: Mit »Reboot« oder Rebellion aus der Krise?

-

Episode 38: Eliten, ein Gespräch mit Prof. Michael Hartmann

-

Episode 35: Innovation oder: Alle Existenz ist Wartung?

-

Episode 18: Gespräch mit Andreas Windisch: Physik, Fortschritt oder Stagnation

Dr. David Edgerton...

- ... at Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin

- ... at King's College London

- ... at Centre for the History of Science, Technology and Medicine

- ... at the British Academy

- Personal Website

- ... on X

- David Edgerton, The Shock Of The Old: Technology and Global History since 1900, Profile Books (2019)

Other References

- David Graeber, Peter Thiel, Where Did the Future Go (2020)

- Conversations with Coleman, Multiverse of Madness with David Deutsch (2023)

- Peter Kruse, next practice. Erfolgreiches Management von Instabilität. Veränderung durch Vernetzung, Gabal (2020)

- Jean-Baptiste Fressoz, More and More and More: An All-Consuming History of Energy, Allen Lane (2024)

-

Vaclav Smil, How the World Really Works, Penguin (2022)

-

John Gray, Black Mass, Pengui (2008)

- Ainissa Ramirez, A Wire Across the Ocean, American Scientist (2015)

-

Thomas Sowell, intellectuals and Society, Basic Books (2010)

- Peter Thiel Fellowship

- Cory Doctorow, ‘Enshittification’ is coming for absolutely everything, Financial Times (2024)

Wednesday Sep 11, 2024

107 — How to Organise Complex Societies? A Conversation with Johan Norberg

Wednesday Sep 11, 2024

Wednesday Sep 11, 2024

This episode fits perfectly into my longer-lasting quest to understand complex societies and how to handle it. I am thrilled about the opportunity to have a conversation with Johan Norberg. The title of our conversation is: How to organise complex societies?

Johan Norberg is a bestselling author of multiple books, historian of ideas and senior fellow at the Cato Institute. I read his last two books, Open, The Story of Human Progress and The Capitalist Manifesto. Both are excellent books, I can highly recommend. We will discuss both books in the wider bracket of the challenge how to handle complex societies.

The main question we discuss is, how can we handle complex societies? Which approaches work, give people opportunity, freedom and wealth, and which do not work. The question can be inverted too: When systems are more complex, is also more control and commands needed, or the opposite?

»The more complex the society, the less it can be organised—the more complex society gets, the more simple rules we need.«

Knowledge and power behave differently, as Tom Sowell puts it:

“It's much easier to concentrate power than knowledge.”

The consequence seems to be:

“If we centralise power we loose knowledge”

We talk about the historic background of the idea of liberty, for instance John Stewart Mills On liberty, Friedrich Hayek Road to Serfdom. Did we lose our desire for liberty? The Austrian philosopher Konrad Paul Liessmann observes:

“Dass das Volk nicht herrschen kann, sondern erzogen, belehrt, bevormundet und mehr oder weniger sanft in die richtige Richtung gedrängt werden soll, ist überall spürbar. Die ubiquitäre pädagogische Sprache ist verräterisch.”

“The fact that the people cannot rule, but are to be educated, instructed, patronised and more or less gently pushed in the right direction, can be felt everywhere. The ubiquitous pedagogical language is treacherous.”

How then, should we think about liberty and responsibility?

“There is only one basic human right, the right to do as you damn well please. And with it comes the only basic human duty, the duty to take the consequences.”, P. J. O'Rourke.

That might be an uncomfortable truth for some, though. Freedom has consequences and responsibilities! The trend of the last decades points to a different direction. Every minute detail seems to be regulated by someone who allegedly knows better:

“Large projects are essentially illegal in California and in Europe”, Elon Musk

The consequence is, as I have discussed in previous episodes, stagnation since many decades. Follow the links below to other episodes. Now, did we become an old, risk-averse, dying society? This would not be good news because:

“With innovation comes the risk of failure”

And the uncomfortable truth is: Our desire to reduce risks might actually increase risks.

“If we are saying that we should not accept anything until it is perfectly safe, that’s the most unsafe and risky bet we could do.”

How can we muddle out of this mess?

“Nothing comes from a committee, nothing from a single genius fully developed. Innovation comes from a process of experiments, trial and error, feedback and adaptation, changes and more people getting involved.”

There is no such thing as an immaculate conception of a new technology.

But what about volatility? Is volatility a risk? For whom? The individual, society? Is societal risk decreasing when we reduce volatility?

What does Johan mean by openness, and why is it Important?

“Openness for me means openness to surprises. This is the only way for societies to thrive and function long term. […] Historically, life was nasty, brutish, and short. We need new things. We need new knowledge, new technological capacity and wealth.”

So why did the industrial revolution happen in the West? What is the connection to openness? What can we learn about control in societies?

“Societies have to be decentralised not top down controlled.”

But Mervyn King discusses in his excellent book Radical Uncertainty the fact, that we cannot predict the future. What happens with innovation that we cannot predict?

“Under open institutions, people will solve more problems than they create.”

Moreover, the opposite is not true. Not innovating does not reduce risk:

“If we would do nothing, we would also be surprised by unpredictable developments. […] We solved the problems that were existential and created better problems and level up. […] I prefer those problems to the ones that made life nasty, brutish and short.”

In Europe, the precautionary principle is in high regard. Does it work, or is it rather a complete failure of epistemology?

But what about capitalism? Has it failed us or is it the saviour? Does the Matthew principle speak against capitalism?

“Elites have an interest to protect the status quo” which is a reason why free markets were blocked in many societies. This does not speak against free markets, but rather is an argument for free markets.

Is the idea of capitalism and free markets more difficult to grasp on a psychological level? Socialist ideas sound nice (when you are in a family or small group) but they do not scale. And even worse, if you try to scale them, do they create the opposite of the desired effect? In a society, we are the kids, and we have other ideas than some authoritarian figure, and we have the right to our ideas.

“The only way to organise a complex society of strangers with different interests and different ideas and different vantage points on the world is not to control it, but instead give them the freedom to act according to their own individual creativity and dreams. […] You can get rich that way, but only by enriching others.”

Moreover, the distribution problem evidently is not solved by top-down political concepts. In authoritarian systems, poverty is equally distributed, but the elites still enrich themselves.

But is trade and economy not used as a weapon on an international scale? How does that fit together, and does that not open up massive risks when we stick to free markets?

“If goods don't cross borders, soldiers will.”

Why is diversification, important, and how to reach it? What happened in Argentina, a very timely question after the new presidency of Javier Milei.

“Argentina should be a memento mori for all of us. […] 100 years ago, Argentina was one of the richest countries of the planet. It had the future going for it”. […] If Argentina can fail, so can we, if we make the wrong decisions.”

There are countries on every continent that make rapid progress. What do they have in common?

At the end of the day, this is a hopeful message because wealth and progress can happen everywhere. Since the turn of the millennium, almost 140,000 people have been lifted out of extreme poverty every day. For more than 20 years. Where did that happen and why? What can we learn from Javier Milei?

“I am an incredible optimist once I gaze away from politics and look at society.”

How can we repay the debt to previous generations that gave us the living standards we enjoy today?

References

Other Episodes

-

Episode 103: Schwarze Schwäne in Extremistan; die Welt des Nassim Taleb, ein Gespräch mit Ralph Zlabinger

-

Episode 101: Live im MQ, Macht und Ohnmacht in der Wissensgesellschaft. Ein Gespräch mit John G. Haas.

-

Episode 96: Ist der heutigen Welt nur mehr mit Komödie beizukommen? Ein Gespräch mit Vince Ebert

-

Episode 90: Unintended Consequences (Unerwartete Folgen)

-

Episode 89: The Myth of Left and Right, a Conversation with Prof. Hyrum Lewis

-

Episode 77: Freie Privatstädte, ein Gespräch mit Dr. Titus Gebel

-

Episode 71: Stagnation oder Fortschritt — eine Reflexion an der Geschichte eines Lebens

-

Episode 70: Future of Farming, a conversation with Padraic Flood

-

Episode 65: Getting Nothing Done — Teil 2

-

Episode 64: Getting Nothing Done — Teil 1

-

Episode 44: Was ist Fortschritt? Ein Gespräch mit Philipp Blom

-

Episode 34: Die Übersetzungsbewegung, oder: wie Ideen über Zeiten, Kulturen und Sprachen wandern – Gespräch mit Prof. Rüdiger Lohlker

Johan Norberg

- Johan Norberg is Senior Fellow at the Cato Institute

- Johan Norberg on Twitter/X

- Johan Norberg on LinkedId

- Johan Norberg, Open. The Story Of Human Progress, Atlantic Books (2021)

- Johan Norberg, The Capitalist Manifesto, Atlantic Books (2023)

Literature, Videos and Links

- John Stuart Mill, On Liberty (1859)

-

Friedrich von Hayek, The Road to Serfdom, Routledge (1944)

-

Thomas Sowell, intellectuals and Society, Basic Books (2010)

- Johan Norberg, A Conversation with Elon Musk, The Cato Institute (2024)

- Reason TV: Nick Gillespie and Magatte Wade, Don't blame colonialism for African poverty (2024)

- Jason Hickel, The Divide – A Brief Guide to Global Inequality and its Solutions, Windmill (2018)

- Victor Davis Hanson on subsidies and tarifs (2024)

- Konrad Paul Liessmann, Lauter Lügen, Paul Zsolnay (2023)

- P. J. O'Rourke, The Liberty Manifesto; Cato Institute (1993)

Saturday Jan 20, 2024

089 — The Myth of Left and Right, a Conversation with Prof. Hyrum Lewis

Saturday Jan 20, 2024

Saturday Jan 20, 2024

Is the political left and right position changing regularly? For many years now, I have been getting more and more uneasy when pundits and journalists use the “left/right” dichotomy. In my lifetime, I have observed numerous political topics that were once at the core of “left” politics that suddenly are named “right” and vice versa.

I then came across the book with the very name “The Myth of Left and Right” and it is a terrific read. So I was very excited that one of the authors, Hyrum Lewis agreed to a conversation.

Hyrum Lewis is a professor of history at BYU-Idaho and was previously a visiting scholar at Stanford University. He received a PhD from the University of Southern California and has written for the Wall Street Journal, Quillette, RealClearPolitics, The Washington Examiner, and other national publications. His most recent book, The Myth of Left and Right (co-authored with Verlan Lewis) was published by Oxford University Press in 2023.

Moreover, this episode fits very nicely with the previous episode with Prof. Möllers on liberalism, so if you are a German speaker, please check this one out as well.

Political realities do not map to a single variable or descriptor—there is no such thing as a political monism. Are “left” and “right” just post-hoc narratives where we try to construct ideologies that are not actually there?

We observe a regular flip-flopping in history; what are prominent examples?

“There is no left and right; there are just two tribes, and what these tribes believe and stand for will change quite radically over time since there is no philosophical core uniting the tribe.”

I, personally, have a profound problem with the term “progressive”, but more generally, what do these terms even mean: progressivism, conservatism, reactionary, liberal?

“It is a loaded and self-serving term […] what is considered progressive changes from day to day.”

“If you don't agree with every policy we believe in […] then you are obviously on the wrong side of history. You are standing against progress.”

So, are left and right not a philosophy but rather a tribe?

Is the definition of conservatism maybe easier? There is a nice brief definition: "Conservatism is democracy of the deceased,” Roger Scruton makes the astute observation that there are so many more ways to screw up and so little ways to do right. But does this help in practice?

“Every person on that planet wants to conserve things that are good and change things that are bad. We are all progressive, and we are all conservative. We just don't agree on what is good and what is bad.”

What are examples where positions are unclear or change over time.

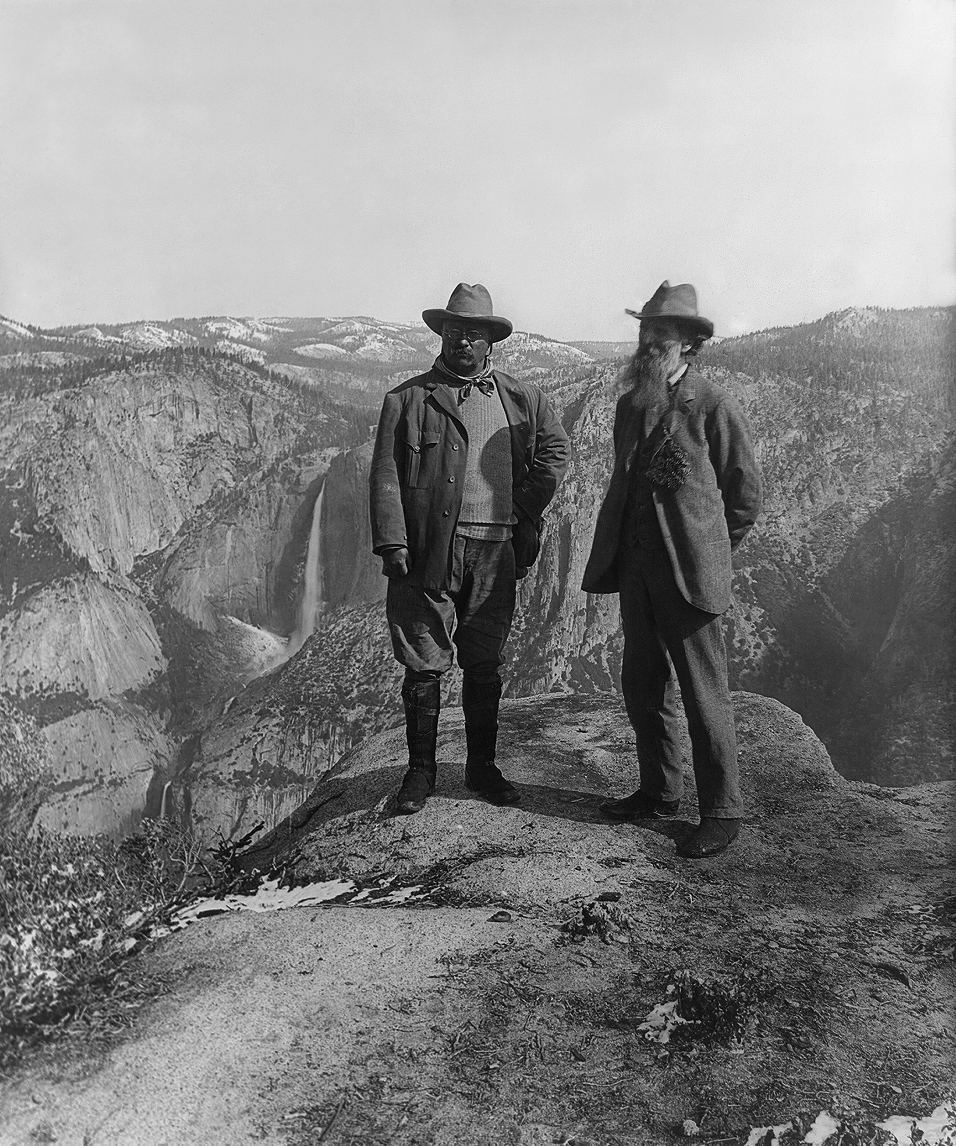

“In 1903, President Theodore Roosevelt visited Yosemite and was guided by naturalist John Muir. The two men spent three memorable nights camping, first under the outstretched arms of the Grizzly Giant in the Mariposa Grove of Giant Sequoias, then in a snowstorm atop five feet of snow near Sentinel Dome, and finally in a meadow near the base of Bridalveil Fall. Their conversations and shared joy with the beauty and magnificence of Yosemite led Roosevelt to expand federal protection of Yosemite, and it inspired him to sign into existence five national parks, 18 national monuments, 55 national bird sanctuaries and wildlife refuges, and 150 national forests.”, Roosevelt, Muir, and the Grace of Place (NPR)

Teddy Roosevelt was a Republican. And here again, a “hiccup”: even though Teddy Roosevelt was a Republican, he called himself a progressive.

In reality, though, if you see someone on the street in a mask, you can predict with high certainty the other political assumptions of this person. How come? Is there now an underlying disposition, or is there not? Or is it much more a phenomenon of tribal or social conformity?

Is the left-right model, at least, useful? What can we learn from past US presidents such as Donald Trump, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush in that regard?

Is the political discourse at least more reasonable at universities and among “elites”? Or maybe even more troubled and more conforming to their very tribe?

If “normal” people are in general “moderate” on important topics (like abortion), why do major political parties play for the few on the extreme ends of the opinion spectrum?

More generally, some educated people describe themselves as “moderate” or “centrist.” Does this even mean anything, and would it be desirable?

What about “realism” vs. “utopianism”?

“Both status quo conservatives and progressive technocrats share a common element: the hostility to open-ended change, guided not by planners but by millions of experiments and trial and error. For both, the goal is stasis, it’s just that one group finds it in the past, the other one in the future.”, Virginia Postrel

A lot of these errors are made under the more elementary mistake that we can know, predict, or foresee the future, especially when we take actions. What can we learn from Phil Tetlock and Dan Gardners forecasting studies?

“To be a true progressive, you cannot be a progressive”

“Our media does not reward granular, careful, and probabilistic analysis.”

So, is it not more significant to distinguish between authoritarian and non-authoritarian politicians or political methods?

But can we be optimistic about the future when non-tribal podcasters like Joe Rogan or Coleman Hughes have audiences that are larger than most legacy media outlets combined?

Is democracy over time the best way to deal with complex situations and challenges? Is there a value in slowness, and are we not just too impatient?

References

Other Episodes

-

Episode 88: Liberalismus und Freiheitsgrade, ein Gespräch mit Prof. Christoph Möllers

-

Episode 84: (Epistemische) Krisen? Ein Gespräch mit Jan David Zimmermann

-

Episode 80: Wissen, Expertise und Prognose, eine Reflexion

-

Episode 57: Konservativ UND Progressiv

Hyrum Lewis

- Hyrum Lewis at BYU-Idaho

- Hyrum Lewis, Verlan Lewis, The Myth of Left and Right, Oxford University Press (2022)

- Hyrum Lewis, It's Time to Retire the Political Spectrum, Quillette (2017)

- Hyrum Lews Blog

Other References

- Roger Scruton, How to be a conservative, Bloomsbury Continuum (2019)

- Johan Norberg, Open: The Story of Human Progress, Atlantic Books (2021)

- Karl Popper, The Poverty of Historicism, Routledge Classic

- Phil Tetlock, Dan Gardner, Superforecasting, Cornerstone Digital (2015)

- Tim Urban, What's Our Problem?: A Self-Help Book for Societies (2023)

- Nicholas Carr, The Shallows, Atlantic Books (2020)

- Roosevelt, Muir, and the Grace of Place

- Joe Rogan Podcast

- Coleman Hughes Podcast